NICHOLAS SULLIVAN

Sullivan and his sculptures

ZEBRA PRINT: Hi Nick, how are you? Tell us everything: your stoves, your cars, the practice, where this all started.

NICHOLAS SULLIVAN: I've been working in a world of these stove forms for the past five years or so. The stove is the vernacular form or framework from which I’m making my own expanded world. The first stove I made I constructed entirely out of paper: I was using paper from the Financial Times in other works at the time, as I was pulled to the tinted pink newsprint they used. It was originally dyed pink to set the newspaper apart from their competitors. I love the simplicity of what I assume is just adding a drop of red dye to a vat of paper pulp and that being the defining aesthetic of this giant media outlet.

🦓: Were you interested in setting your work apart?

NS: I think initially I found it to just be a beautiful material, so I experimented with it, wanting to push on the edges of what something like that could do or hold in regards to material manipulation. I started by rolling single sheets as tight as possible, the way you roll cigarettes. It was a solid tube that ended up, structurally, in many ways like a quarter-inch round bar of steel. The original batch of those stove forms was made with this rolled paper as armature. Then I used the same Financial Times pages to close the form off across the armature to create the closed volumetric object.

🦓: So you used paper as both this structural and planar material. Why the stove?

NS: Right. I arrived at the stove form by following the work that I was making prior, having experimented with paper and touching materials like oak and charcoal as well. I had made some objects that were less directly nameable prior, and I wanted to inject something truly vernacular. I liked the basic intensity of a stove being made from paper, which could ignite and basically “become” the charcoal or carbon I used to rub the paper with afterwards. It is a basic kind of binary recycling logic that I tested to see if it felt dumb or exciting when brought to fruition. I also grew up with a woodstove in a house that my dad built. It was the only source of heat in this house, so I think maybe it burned itself into my lizard brain.

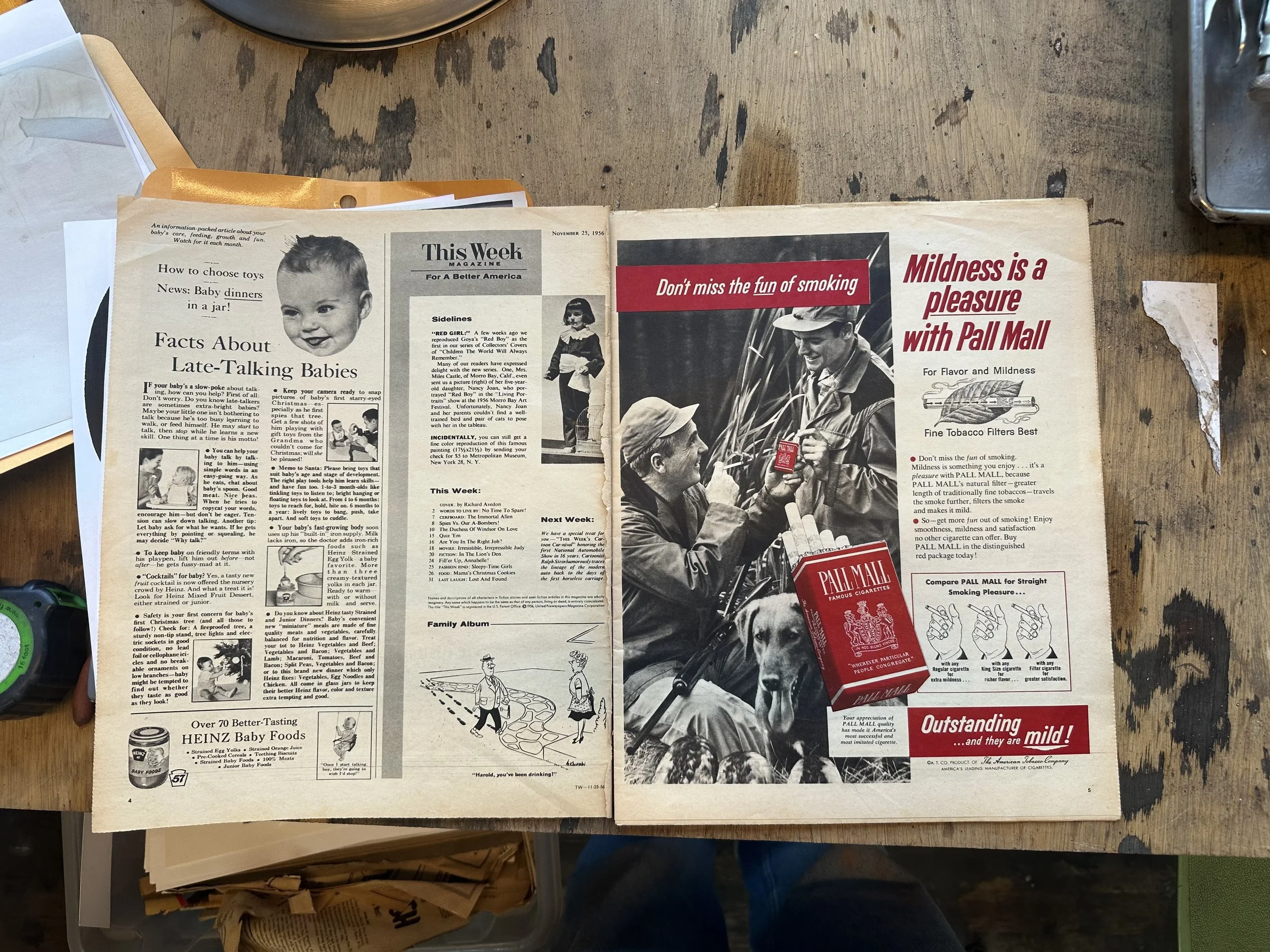

🦓: You’ve done stoves, vintage cars, irons, sinks. You also don’t just use the Financial Times anymore, you collect vintage newspapers and paper mache with 1950s to -70s newsprint. Are you interested in domesticity at all?

NS: Yeah, domesticity or utility and these artifacts of an aspirational future that failed. They feel dated to the nuclear home, American exceptionalism, a raging free market, et cetera. I think it’s a really interesting moment, where we’re at, because my generation is the first resounding failure from the post-war projection Americans were sold, you know? The collapse of hegemonic idealism.

🦓: And in these old newspapers, those concepts are really hammered into everything.

NS: Exactly. So I think it’s interesting to reuse these images and objects in the world we live in now. The coal iron to me represents a similar thing to my stoves: an object whose transition from utilitarian object to purely visual object is happening in real time. It is a moment of ecstatic transformation to pure form.

🦓: Right. They’re also all homes for heat, all these forms you make, and you play with charcoal in some of these initial ones.

NS: Exactly. States of combustion, state changes in general, just like a body too. Again, the intended utility of all these objects felt so rich for me to base a form around. I found that the combination of the paper stove form, the collage, and the rubbed charcoal or pigment snapped the parts of the object together into a complete whole, like a totally new thing was born. That moment was alchemical—even addicting for me—so I’ve been pushing around that formal and material world to tune the objects, or “sharpening the knife,” as I like to say. I’m sure other artists have this experience as well, where parts of experiments and questions come together and snap into a whole. The object then begins to manufacture its own language outside of you. That’s when we start getting to the good stuff!

🦓: That’s a great origin story for a series of sculptures. Recently, you’ve been exploring these forms still, but pivoting from newsprint to steel and metal. Are you exploring the idea of reinforcement, perhaps “stronger” materials? Or are you jumping off this 1950s Americana idea, are you making a statement on industrialization?

NS: I’ve been experimenting with that a little bit, painting with car paint, playing with bondo, which is a body filler for car and household repairs. The surfaces have always been about collage for me, but they would get into this strange state because paper also responds to moisture. I would seal them in a box, and they would buckle with time. My friend Charlotte suggested I fortify the armature a little bit. I was worried they would lose their spirit, but it actually opened up some new material worlds for me.

🦓: Clearly, they didn’t!

NS: Right! There was something so beautiful about how fragile these initial paper sculptures were; they felt like origami. You can really feel the integrity of a singular material. I was so resistant to losing that. So I got to these slowly, with round bar steel as the new armature. I stretched paper over those points as I had done with the original paper forms, but of course, they’d still buckle, because it’s suspended paper over these points of tension, so I pivoted and sheet-metalled one.

🦓: Was this all self-taught?

NS: I didn’t study metalworking. I worked in a woodshop, I did some foundry work in grad school, but I really am teaching myself all these techniques. I love working: I love repetition and focus, and I love learning how to make things in new ways. What was crazy to me was seeing how unbelievably malleable steel is. I've cut and welded this form to get the scale fine tuned basically a million times.

🦓: The skeletons for the forms seem to warp—some of these here in your studio, the one currently on view at International Waters is elongated, almost twice the height and a quarter of the length. Is this something you’ve changed over time, or just experimentation?

NS: Well, at first I made some works and they would drive me fucking crazy, because it felt like the proportions were all wrong. So then I experimented—cutting the center of these stoves out, welding seams together. For my recent show at CLEARING, I made that 10 foot sculpture, welded and collated. I scaled up the proportions of an older stove I thought worked well but was only 20 inches tall…

Left to right: Iron Fan (color), 2023;

Brown Stove, 2023; Plaid Stove Black and White, 2023

🦓: With these old newspapers, did you find yourself gravitating towards specific genres that you’d cut out, like advertisements or classifieds? And do you feel like now that you don't have that, like there's solid colors that you, you said you, you know, spray or whatever, car paint. Like, is that language different for you? Does that make sense?

NS: Yeah, totally. It lands the object differently. Like those paper sculptures: the fusion between the paper, the image, the charcoal, and the form all snapping together feels like this magic event that happened. I think of that as collage. With paint and bondo it all becomes a very different thing but through the same mind of making. I just stayed in my world and followed. When I’m choosing imagery it depends on the form, sometimes I’ll stay all in one territory (like all car accidents) or other times I will pull the images based on their color image quality (heavily half toned, blown out, close up etc).

Iron Bug, 2025

Gloss Ear Stove, 2024

🦓: Favorite car, art historically?

NS: Oh, there are many. I would say Robert Grosvener is my king of the car world. I think he's such a strange and amazing artist that continues to preserve this enigma in a very important way, a way that’s very much out of vogue with young artists now. It’s something that I don’t want to be lost to this new generation of artists: to not have to explain your decision making, to allow things to just be. To allow them to manufacture their own language.

🦓: How so?

NS: In his press release for his most recent show at Paula Cooper, I believe, they wrote this big thing that was all jargoned up. The quote from him, though, that opened the press release was something like, “I do this just for fun.” Pure hardcore honesty. Much appreciated by me, and that’s not to say I think those objects are un-intellectual, quite the opposite. There’s that Pipilotti Rist video, too, where she has the big flower on a long stalk. She’s in this long dress and walking or dancing down the street smashing car windows. There are of course so many more (Richard Prince Hoods, etc. etc.)

🦓: Beyoncé's Lemonade.

NS: Ha, exactly!

🦓: Do you care for car crashes? Chamberlain is up there for me.

NS: Warhol’s car crashes are some of my favorites. I’ve recently slid him into my top three favorite artists of all time. There’s the obvious world of him, the power of his presence and all that, but his practice was so massively expansive and strange and relentless and so much of it is so good. I can spend five years making fucking stove forms, and I get like five that I really like. I've made so many.

🦓: Tell me more about repetition. It seems to be crucial to your sculptures, with all these varieties of cars and forms and Xerox prints.

NS: Repetition is religion, and it's the way to everything good. Repetition, in my mind, expands outside my objects and images and into everything else. Sanding these down is repetition, for example. Wearing everything down, to groove something into your mind. Apply this logic to anything and you find repetition at its root.

Jane Doe 1, 2, 3, 2025

🦓: Have your inspirations changed since you were younger, or the things that motivate you?

NS: Yes, music inspires me for sure, or attitude. I've always been interested in attitude, or maybe about being direct which is built into the foundations of punk and hardcore music. I love going to punk and hardcore shows. There is an intensity of belief and a focus on the present that I find resonates deeply with me. In my head, there’s a connected world of why I'm pulled to punk and the things I like to make.

Green Stove, 2022 (left); Flower Sink, 2022 (right)

NS: I’ve been a nerd about art history for a long time, and I think one of the most incredible things about art making is that you get to inject yourself into the canon with the artists you love simply by making your own art, and it can build on what they did, and you can point to them with your work. I have always been really interested in pulling the connective tissue in great American sculptures closer to me.

There was a moment, when I was a senior in college, when I found a voice that felt like mine. I started to make things that really felt like they were coming through me, not through school or not through some affected voice. It was this incredibly energizing feeling. I listened to this one Minor Threat song over and over and over in my headphones when I was making stuff, just one song for a year. There is a line in that song that goes, “You tell me that I make no difference / Well at least I’m fucking trying / What the fuck have you done?”—I thought about this all the time while I worked. I felt so empowered, making so much. I fed on that feeling for so long, and I still do.

NS: I feel like we’ve sacrificed a vivid world, for the sake of, like, pennies. We traded it for pocket change. Years ago, we lost all this beauty in exchange for ease of production. But I want to hold onto that. I had a professor in college who succinctly described what happens when you start to make work for someone else and the object loses its relationship to you. He said, “It's like putting your hand in your pocket and finding someone else's hand in there.” I don’t ever want to get there. The repetition is practice to keep going. The power of that is monumental.

Nicholas Sullivan (b. 1987, Connecticut, United States)

nicholas-sullivan.com / @hows_nick

Nicholas Sullivan is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, NY. Sullivan earned his M.F.A. in Sculpture from Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Boston, MA, and his B.F.A. in Sculpture from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA. Recent exhibitions include; Chrysler (solo), CLEARING, New York, NY; Everblue (two person), International Waters, New York, NY; Planes, Trains and Automobiles, Galeria Mascota, Mexico City, MX; Make Hay in the Sun, HG (two person), Chicago, IL; Comfort Animal (solo), A-L Gallery, Seoul SK; The World Without Us, Brennan & Griffin, New York NY; Gist & Gesture, Kavi Gupta, Chicago, IL; Foster Prize Exhibition, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA.