JUSTIN CHANCE

Chance in his studio

ZEBRA PRINT: You once said you start with titles and then create your work from there. Does that still ring true? Can you walk me through some titles that have been relevant to you?

CHANCE: As a writer, words are really important. I’m bad with numbers and spatial reasoning, so I find myself mostly thinking through projects mostly in language and colors. Not always, but sometimes phrases and words that I find interesting come to me and then I work from there. When a word hits me, I work to figure out if it’s better off in its original context or if I can visualize the word somehow. I’m asking: how would a sentence or word live, narrative-wise?

🦓: Was it a practice in translation?

CHANCE: Translation, almost, and now the work has grown. Recently I’ve been trying out incorporating text directly in the work, which re-contextualizes each piece.

🦓: So you began with the quilts, then explored more of your current text-based work?

CHANCE: For a long time, it was about deciphering my problems with the historical significance and discourse surrounding painting. I realized, after a while, I was putting a lot of stock in the titles of the work, when if I wanted to explore a piece of text, I could just incorporate it into the works themselves.

Dystopia, 2023-2025

Felt and paper in Chance’s studio

🦓: Can you tell us about your recent exhibition “Again” at Tara Downs?

CHANCE: Yeah. That exhibition featured a piece where I outlined a version of the alphabet, similar to the charts children see in school when they’re starting early education. That was really exciting, because it gave me an opportunity (and excuse) to break down my interest in language and its possible theatrics. For instance, V was for Visits, which featured an illustration of an alien, thereby implying its own kind of narrative. Inversely, the alphabet is also missing letters that, when rearranged, end up spelling JUSTIN.

🦓: There’s something happening there, an exploration of didactics.

CHANCE: Right. The narrative of that piece circles around its title, “Dystopia.” I’m interested in the everyday, and when you’re a child, you think your everyday is everyone else’s everyday. I’m just now catching up to an awareness of these things. I’m not good at being present, and you can see that in my work, where it’s all about hindsight, the digging down of old things.

Magic, 2025 in progress

🦓: What other signifiers of everyday life have you been thinking about?

CHANCE: I had a show in London last year that explored this through a postcolonial lens. I think a lot of signifiers for what the everyday means can be found in language-learning books and tools. Childhood and children’s media is a deeply instructional period. They’re teaching you how to be a person. Presently, I’m very interested in how that happens to go hand in hand with the Information Age we’re finding ourselves in.

🦓: In a world where you can find evidence to basically believe whatever you want, childhood is probably the only time we’re taught the same thing.

CHANCE: Yes, exactly, but it also depends on where. What I’m trying to do more now than ever is to give myself permission to employ more of these visual signifiers. People often talk about the childhood element of the work, but for me, Dystopia means to evoke sort of a book report situation. Think informational posters with standard font and formatting that you’d see hanging up not only in classrooms, but also elsewhere.

🦓: Are you interested in play, or the experience of childhood in itself?

CHANCE: Yes, but again, with respect to its everyday aspects. More in that childhood exists as a period of time that everyone has experienced. I’m not obsessed with childhood itself, really. I hate when people talk about their inner child, or anything regressive or self-infantilizing like that. I don’t care. For example, a hand-embroidered piece from the show Again at Tara references the aesthetics of basic word art tools in Microsoft Word and MS Paint. That’s stuff we used to do on our computers when we first had access to them, you know? Writing your name in an empty PowerPoint and making it wavy and giving it a gradient. Exploring that stuff with the agency and creative freedom that comes with being an adult has been interesting.

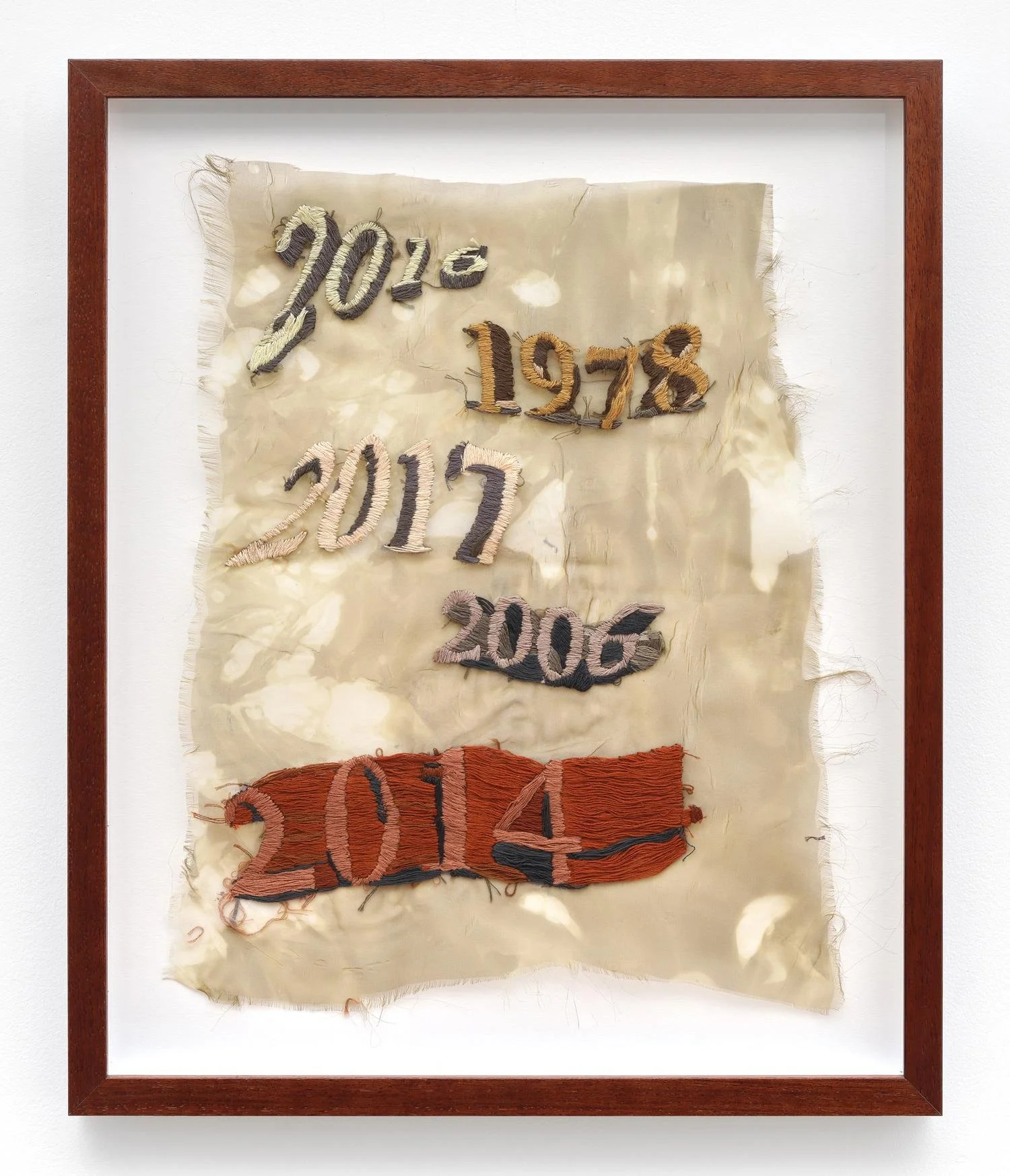

Police Shootings, Mass Murder, Cult Massacre, Religious Scandal, 2024-2025

CHANCE: The embroidery is titled, “Police Shootings, Mass Murder, Cult Massacre, Religious Scandal.” I know exactly which events correspond to which years, but am also aware that the average viewer probably wouldn’t think of the same dates as I would, because bad things like these happen all the time. Again, see this notion of the everyday and repetition.

🦓: Do you research specific histories or events that apply to subject matter you’re interested in, or social markers that you find important to your work?

CHANCE: The thing with these events that I’m thinking of is that I’ve already decided on them in my head. I have the references prior, so the embroideries with dates are a great experiment in backwards thinking. Let’s call it the inverse of research. To put it another way: I started the piece knowing the title would be “Police Shootings, Mass Murder, Cult Massacre, Religious Scandal;” it was just a matter of figuring out which dates from each of these events to use. There were so many to choose from.

🦓: Are these dates and words important to you as a signifier of markers in present-day culture, or are they more about specific themes you allude to that end up being notable about what you embroider?

CHANCE: Overall, though especially for the show Again, I was largely interested in exploring ideas of violence, repetition, and the possible banality of bad things. Like shock as a finite resource. The passing of time as a potentially violent actor, or even time as a possible accomplice to violence. I think it’s also important that the work is able to exist on different levels. On one side, you have the rudimentary book report, a clip art-style visual language. On the other hand, I really want to boast something else, like a deep technical understanding and reverence of the kinds of things that I’m referencing.

🦓: I assume this is where your quilts come in. How important is technique to you with regard to the work?

CHANCE: Technique is really important in the work overall. Conceptualism matters a lot, but it’s important to me that the work is able to flex some sort of technical muscle of its own. It was very important that the quilts followed the rules and definitions of what I was taught constituted a quilt: three layers, unified by one stitch, et cetera. Those parameters were so helpful in the beginning. Tension is also important. For example, with “Dystopia” and “Police Shootings…,” it was important that the work would be easy to read—very legible—but at the same time, very technically rigorous. Embroidering is incredibly time consuming. It all comes down to wanting my work to be both conceptually and technically impressive.

🦓: What’s the connecting thread between all these different forms and mediums you play with?

CHANCE: Hopefully, a kind of tone. The work is probably all over the place, but I like to think that these ideas are all related. Hopefully there’s a unifying through line. Things that are almost so banal, to the point that they’re novel: that's my sweet spot. That’s when I feel like an idea is on to something. Just as I wouldn’t be interested in reading a text written entirely in gibberish, I don’t really find anything satisfying in making entirely abstract work that has no reference to anything else. I’ve found that using real things that reference other real things can be a really helpful tool or tactic to help the viewer and reader develop enough bandwidth to eventually engage with the poetic.

🦓: You’ve mentioned earlier that an interest in the contemporary everyday also involves an acknowledge of colonialism and post-colonial theory.

CHANCE: I think they go hand in hand, because ultimately it begs the question, “Whose everyday?” Who normalized these standards? My mother’s from Jamaica, and my father’s from Trinidad. When my parents were born, those countries were still colonies of England. Then I’m born in America, whose identity is founded on its separation from England. Once again, this separation situation presents itself, and also this notion of common origin. For my London show, I was interested in toying around with this idea that maybe post-colonial studies could be explored through some sort of Lacanian mommy-issues lens. That’s where the title Motherhood came from.

Commonwealth, 2020-2024

🦓: Can you share more about that show?

CHANCE: The standout, to me, was this piece was called Commonwealth, named after the British Commonwealth, which is made of over forty nations that were previously British colonies. The piece features 54 butterflies, each butterfly endemic to a nation in the Commonwealth. It allowed me to combine my interests in project-based research, language, and a more methodical approach to conceptualism.

🦓: Why butterflies?

CHANCE: The most obvious is their connection to metamorphosis as well as migration for some. In addition to that, I found it interesting that some butterflies have names that reference underlying motifs of power and violence, these references to colonial, noble, militaristic, or religious status. For example: Monarch, Viceroy, Dusky Friar, Common Commander—you get the gist. The piece also included an index detailing which butterflies corresponded with which colonies, which goes back to my interest in visual information. This really pushed me to experiment with how I could take creative control and still be satisfied with what’s being conveyed.

🦓: I’m intrigued by the data points and references in balance with what the work conveys. Would you change the work if you found out people were reading the pieces incorrectly?

CHANCE: I like to say that people can read the work however they want, but I don’t want them to read the practice wrong. I don’t want to seem like some sort of random eccentric with three thousand interests and disjointed references. A large motivation I have regarding language now includes making my messages and through lines more obvious. If the point is understanding, or if the idea behind the work is important to me, I want to find a way to make that more known. In that vein, I think the quilts I make are very formal, and so they tend to really shift people’s attention. I would like the viewer to be able to get beyond an initial impression from just the handiwork. I’m not complaining, of course, but it would be a real superpower to be able to switch the aspects of your practice that people are drawn to. I want them to go wow, so smart. What a researcher and scholar. It’s tricky!

🦓: Are there any other works in that show you would like to highlight?

CHANCE: Yeah, this quilt titled Mum’s House. Drawn in dye marker are words taken at random from a list of Dolch sight words. Compiled by Edward Dolch, this is a list of around 200 words that have to be included when you’re teaching literacy. They include words like apple, paper, and rain. Dolch believed these were basic words that knowing would allow for an easier experience learning to read (and therefore, learning more words). The building blocks of language, you can call them. I wanted to present this alongside Commonwealth.

Mum’s House, 2024

🦓: Is it about language itself, or also the remnants of the British Empire?

CHANCE: Both. I think we’re perpetually going to live in this reverence of English-ness. It’s been interesting to understand that the ubiquity of the English language stems from the ubiquity of English imperialism. Again, an everyday situation that carries with it all these possible ideas of violence in plain sight. The idea of us all being taught the same thing, the first of which being a language, is something worth thinking about. Outside of their names, the butterfly element also references the idea of breaking something down to emerge as another.

🦓: Metamorphosis.

CHANCE: Cocoons are kind of disgusting, but they allow for the emergence of this creature that we’re all supposed to understand as beautiful. Apparently, inside the cocoon, there’s a period in which the insect is completely liquid—I’m talking totally dissolved. To this day, scientists can’t fully detail everything that happens in there. But I love the reference to this liquefaction, this violent action of breaking everything down and reforming its muscles to become Another Thing. The subtext of all that in conversation with colonization, plus migration and pollination: all of that was fascinating to me.

🦓: What have you been working on recently?

CHANCE: Things are kind of a mess right now, but lately I’ve been back to making these woven drawings: these sheets of paper that I’ve been weaving together. I create the same drawings on two types of paper, one transparent and one very opaque, and I weave them together. It’s how the butterflies of Commonwealth were made. I’ve been working on a few experiments, testing things out for future shows. I suppose conceptually, I’ve been thinking about adulthood, and I’ve been trying to figure out ways to get these new ideas into the work. This handmade, almost analog, approach to technology. I feel like I’m a part of the last generation where social media was not always a part of my immediate reality.

🦓: How would you describe your relationship with social media as an artist?

CHANCE: When I have a show or deadline, I deactivate completely. I make sure my account is gone and unsearchable. About two weeks before a text gets published or a show is about to open, I reactivate and start to post. I post a lot of my work on Instagram, I’m not crazy. That being said, I’ve always said that I think Instagram is the mall. It is not your friend, it is a corporation. The relationship we have with social media now is bizarre; I’ve said this before in other interviews and I will say it again because I think people have forgotten. Instagram is the mall! You go there to shop and see hot strangers who go to schools you’ve never heard of. You don’t go to J.C. Penney’s or Macy’s for therapy. It is a tool for shopping. It is not a neutral environment, it’s a digital platform for data and the exchange of commerce. Log off. You can’t put all your eggs—and all of you—in that basket.

🦓: OK, great analogy. It can’t be a crutch or something you resort to.

CHANCE: Yeah, that, absolutely.

Justin Chance (b. New York, New York)

justinchance.com / @_justin_chance

Justin Chance is an artist and writer based in New York. Chance earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts and Bachelor of Arts in Visual & Critical Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015. Chance’s work has been the subject of solo and two-person exhibitions at the following venues: "Again", Tara Downs, New York, US (2025); “Archive,” Naranjo 141, Mexico City, MX (2024); “Live,” Tara Downs, New York, US (2023); “Love is Sci-Fi,” Sydney, Sydney, AU (2023); “Winter (with Sylvie Hayes- Wallace),” Hesse Flatow, New York, US (2023); CFA, Milan, IT, presented by Tara Downs (2022); “Social (with The People of New York),” Apparatus Projects, Chicago, US (2022); “Low Life,” Smart Objects, Los Angeles, US (2021); and “Better (with Hunter Foster),” Gern en Regalia, New York, US (2021). The artist’s work has been presented in numerous group exhibitions including: “The Principal Cause of Serial Monogamy,” Tara Downs, New York, US (2024); “A Study in Form (Chapter Two),” James Fuentes, New York, US, (2024); “FLESH & FLOWERS,” Made in America, NO NAME, Paris, FR (2023); “Public Life (Drawings), Chris Andrews, Montreal, CA (2023); “The Grid and the Curve,” JTT, New York, US (2022); “Material Knowledge,” Arsenal Contemporary, New York, US (2022); “Elective Affinities,” Chapter NY, New York, US (2022); “Remnant, Artifact, Flow,” Thierry Goldberg, New York, US (2021).